Sporting Dogs - Optimum Nutrition for Optimum Performance - By Lisa Hannaby Aird

Jul 15, 2024

Whilst the American Kennel Club uses “sporting” to cover those breeds who generally hunt or retrieve, I’m suggesting that any dog who engages in a sport is a sporting dog. You should therefore tailor their nutrition accordingly.

Why? Well, have you ever hit a wall when out on a run? Or plateaued in your own gym training? Or simply get that mid-afternoon slump? Well, I’d bet that you’re simply not fuelling sufficiently for your lifestyle. This can range from not having enough fuel (macros), to not having sufficient co-factors to make that fuel, or just using the wrong fuel for the energy system you are demanding from.

This can also happen with our sporting dogs; but they can’t tell us they hit a slump, or that they feel like they are running on empty. Instead, they tire, they get injured, they recover slowly, they become stressed/aggressive and they just plateau no matter how much training you seem to put in.

This whole topic could be a book, but to start off with, we’re going to look at canine energy systems, how to fuel those systems, the importance of both macros and micros, supplements and feeding strategies.

Canine Energy Systems

The body uses a mixture of carbohydrates, fats and protein as sources of energy. The balance at any point in time depends on intensity of activity, availability of fuel type, and genetics. And yes I said the dreaded C word! But if we’re talking about sporting dogs, we must talk about carbohydrates, so can you give me the benefit of the doubt for a moment?

Available carbohydrates can be quickly and easily converted, providing immediate energy for high-intensity activities.

Fat takes longer to convert and supplies energy to support low to moderate intensity exercise.

Protein can also be used to provide energy, but the body would generally prioritise other protein functions first (like immune function and alike).

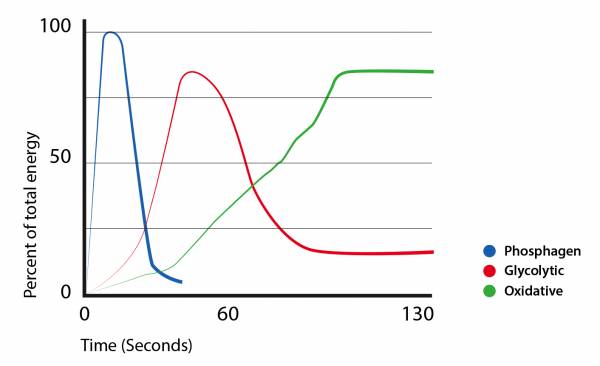

There are three systems for generating energy, each of which has a different biochemistry and rate of ATP production:

Phosphocreatine

The phosphocreatine system uses creatine to supply a phosphate group to recycle ADP to ATP and release energy. It is able to generate energy quickly, but only for a short period of time. This is useful for high-intensity activities such as weight training or sprinting.

Creatine synthesis can be impacted by various factors including a sufficient supply of vitamins B9 (folate) and B12. Creatine can also be obtained directly from the diet (meat).

Glycolysis

Glycolysis is the breakdown of glucose to generate energy. It can be anaerobic or aerobic. Anaerobic glycolysis is the major source of energy during strenuous exercise without the use of oxygen. Glycogen is broken down into glucose and rapidly converted to ATP. However, as each glucose molecule only produces a small amount of ATP, it is inefficient. After a few minutes of exercise, the body starts to switch over to the aerobic system.

Aerobic

When oxygen is available, the body is able to generate ATP by breaking down carbohydrates and fat, aerobically.

Initially, most energy production is fuelled by muscle glycogen. After about two hours of high-intensity exercise, the fuel source switches to carbohydrate and fat (lipolysis). Although fat is energy dense, its conversion to ATP is slow compared to carbohydrate.

This graph is developed with human athletes in mind. As usual, we’re a little behind in the canine world. But we know the same applies in dogs, how? Well, we look to speedy and sled dogs for comparison.

Speedy dogs have a higher number of fast-twitch muscle fibers. Fast twitch muscle fibres rely on glycolytic processes and therefore have fewer and considerably smaller mitochondria (yes, we all remember it from school, the mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell).

Sled dogs on the other hand have a higher number of slow-twitch muscle fibers. These are mainly oxidative and contain vast quantities of large mitochondria.

So, speedy dogs are better at sprints and sled dogs are better at endurance. Of course we know that, but this clarifies that we need to support the speedy dog’s ATP and glycolytic system, and we need to support the sled dog’s aerobic/oxidative system.

For example, when we feed sled dogs too many carbohydrates (to the detriment of fat) they can develop signs of ‘tying up’, coprophagy and hypoglycaemia during intense exercise. This typically resolves when carbohydrate content is reduced.

On the other side of the scale, one study demonstrated that greyhounds were 0.18 seconds slower over a distance of 500 m when fed a diet with increased protein and decreased carbohydrates.

To date, all other canids (which includes pretty much every breed of dog we’re considering when we say sporting dogs), apart from greyhounds, have similar muscle fibre composition. So we can make a very easy generalisation for all canine athletes.

For all dogs, you must prioritise good quality protein (fresh meat).

Afterwards, the order in which you should prioritise macros would then be:

For most breeds: fat and then carbs.

For speedy dogs: carbs and then fat.

Protein

Physical exercise stimulates catabolic processes in the body, and protein is literally the building blocks of the body. Therefore, an adequate supply of high-value protein should always be taken into account when a diet for a sporting dog is composed.

The amount of protein provided with food must compensate for losses and provide

substrates for building new proteins. Therefore, dietary protein has mainly building functions in the canine athlete and to a much lesser extent, it acts as a source of energy.

As stated by various researchers “the best source of high-quality protein for dogs is meat.” But don’t forget eggs are a great source of protein too.

But how much?

Well, it isn’t an exact science, but here’s what some of the literature discusses:

Racing sled dogs require a high protein diet because anaemia can develop during training in dogs fed a low protein diet. In one study, haematocrit declined in dogs fed a diet containing 28% of energy as protein but not in dogs fed a diet containing 32% of energy as protein. This “sports anaemia” was also more marked in dogs fed a vegetable protein diet compared with an animal protein diet. Read: feed animal protein to your sporting dog, not plant protein.

In addition, plasma volume has been found greater in racing sled dogs fed higher levels of protein (40% of energy). Why is this important? Well, the more plasma you have, the greater your overall blood volume. This leads to an increased stroke volume with less cardiac effort. With more blood volume, you have a higher VO2 for the same level of effort. Essentially, you have more aerobic power. So sled dogs have more power! Win win!

It’s also worth noting however, that greyhounds have been found to run slower when fed increased dietary protein (37 vs. 24% of energy).

The Study: Dogs were fed a high-protein (37% protein, 33% fat, 30% carbohydrate) or moderate-protein (24% protein, 33% fat, 43% carbohydrate) extruded diet for 11 weeks. Dogs subsequently were fed the other diet for 11 weeks (crossover design). Dogs raced a distance of 500 m twice weekly.

Results: Greyhounds were 0.18 seconds slower (equivalent to 0.08 m/s or 2.6 m) over a distance of 500 m when fed a diet with increased protein and decreased carbohydrate.

But remember, this was an extruded diet, can we make the same assumptions about fresh food? In addition, when we know what we do about speedy dog’s and their muscle fibers, was it more the reduced carbs as opposed to the increased protein?

Fat

For the canine sprinter, you would opt for lower levels of fat, for the sled dog, higher levels of fat.

One brief report suggests that greyhounds run faster when fed a moderate fat (31% of energy) diet compared with a very high fat (75% of energy) diet.

Sled dogs on the other hand seem to do well with higher levels of fat.

A high fat/high protein diet containing no carbohydrate resulted in better performance and less evidence of exertional rhabdomyolysis when fed to sled dogs.

This also translates somewhat to farm dogs. Some researchers hypothesised that feeding working farm dogs an ultra-low carbohydrate/high fat diet would reduce their interstitial glucose concentrations (IG) which in turn would reduce physical activity during work. But, their study proved them wrong, a little. Whilst IG levels did reduce, their activity did not. The researchers concluded that working dogs adapt quickly, and they became a dab hand at using fat for energy!

When we say fat, we’re looking at fat included in meats (duck and lamb generally have a higher percentage of fat that other meats), you may also include oily fish, plant based oils (hemp seed or flax seed), nuts, seeds and if you cook your own bone broth, skim the fat off the top, let it set and then freeze it in moulds. You can also include MCT oil and eggs contain fat too!

Carbohydrates

A note on carbohydrates

There are two groups of carbohydrates. Available and unavailable.

Available Carbohydrates

These are digested and absorbed in the small intestine. Their main function is to provide energy. Most tissues metabolise glucose for energy, but the brain and red blood cells have an absolute need for glucose. Carbohydrates can be stored as glycogen (in animals) in muscles and the liver, and these stores can be accessed when circulating glucose is low.

Unavailable Carbohydrates

Unavailable carbohydrates are non-digestible carbohydrates which include soluble and insoluble fibre.

Insoluble fibre like cellulose cannot be digested, it adds bulk to stools and promotes bowel health. Insoluble fibre also attracts water to the stool, making it softer and easier to pass.

Soluble fibre can be broken down (fermented) by the large intestinal bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

For the canine athlete, you can utilise both available and unavailable carbohydrates, but the closer you are to competition or training, the more you use available (like oats) as opposed to unavailable carbohydrates. You don’t want unavailable carbohydrates sitting in the digestive tract on game day!

Some demonise carbs, and this also applies in the human world. Tim Noakes literally wrote the book on carb loading and he has retracted some of what he said. But carbs aren’t just those beige foods we find in both the canine and human world, carbs like fruit and veg contain cracking phytochemicals that are great additions for the athlete.

The other point to note is that the digestibility of carbohydrate in extruded dog foods is variable, and not all starch is digested in the canine small intestine - and that, you really don’t want sitting in the digestive system on game day!

In addition, increasing data is highlighting that, for dogs running in multiple heats on a single day or over several consecutive days, immediate postexercise carbohydrate supplementation may promote more rapid and complete recovery between bouts of exercise.

We must also remember that for macros to do their jobs in the body, they need the help of certain cofactors.

Cofactors for Energy Metabolism

Remember the krebs cycle? Well, if you were listening in school it's the series of biochemical reactions that release energy stored in nutrients through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats and proteins. For the krebs cycle to work as it should it needs certain vitamins and minerals. Some of the players are below:

Magnesium

Magnesium is seen to enhance the activity of the enzymes involved in energy metabolism. All reactions involving ATP require the presence of magnesium. Studies have demonstrated that when extracellular magnesium is removed, the process of glycolysis and the transport of glucose is significantly inhibited. In addition, ATP must be bound to magnesium for it to be biologically active.

The issue with magnesium is that the body essentially dumps it when stressed and many sporting dogs are stressed (good stress or bad stress, it all has the same impact on the body). From experience, many sporting dogs are low in magnesium, which compromises energy production and more and so this trusty mineral should garner some attention in the canine athletes diet. You can feed magnesium rich foods like spinach, swiss chard, kale, pumpkin seeds and tuna or consider supplemental magnesium under the guidance of a professional.

B Vitamins

B vitamins are the MVPs when it comes to energy metabolism. They are involved in various steps of the krebs cycle and like magnesium, when stressed, the body uses high quantities of B vitamins. For this reason, the canine athlete can often be low in these trusty vitamins. Meat is a great source of B vitamins (so raw fed dogs often get a decent dollop of them), as are seafood, poultry, eggs, leafy greens, seeds and nutritional yeast (which is becoming an addition to many canine supplements on the market). You can also supplement B vitamins for the dog and as they are water-soluble, the risk of toxicity is relatively low. I would always recommend a methylated version of B vitamins as they can get to work quickly in the body and you bypass any potential genetic glitches compromising utilisation.

Iron

Iron influences key enzymes in the krebs cycle, contributing to its efficiency. Iron supports mitochondrial oxygen consumption and ATP formation.

There are two sources of iron:

Haem is found primarily in meat and meat products

Non-haem is found in plants.

Haem is generally well-absorbed, whereas non-haem absorption is largely affected by other factors.

Common inhibitors of iron absorption are phytates, tannins, starch, and proton pump inhibitors.

Phytate binds to minerals, rendering them less available and they are commonly found in nuts, grains, pulses and tubers. Whilst tannins have been suggested to have antioxidant properties they play an inhibitory role in iron absorption. That said, unless you offer your dog tea on a regular basis, tannins are unlikely to be an issue.

Proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole) do exactly what they say on the tin. Gastric acid is secreted from cells found in the stomach. These cells contain proton pumps to secrete this very acid. Proton pump inhibitor medications come along and turn off these pumps, which stops the secretion of gastric acid. Unfortunately, stomach acid is important in releasing iron from ligands in food and in solubilizing ferric iron by converting it to ferrous form, so low levels of stomach acid can impair iron absorption and utilisation.

However, studies have demonstrated that when a multivitamin was administered alongside PPIs, iron absorption was not affected. The vitamin C found in the multivitamin is thought to be protective even alongside PPI medication. Vitamin C is seen as a potent facilitator of iron absorption because ascorbic acid reduces ferric to ferrous iron, which is therefore absorbable.

CoQ10

Coenzyme Q-10 (CoQ-10 or Ubiquinone) acts as an electron transporter (in the electron transport chain which leads to the production of ATP). Basically it shuttles electrons where they need to go to ensure energy is produced. In addition, it functions as an antioxidant. We’ve noted this from feedback throughout the body. When the generation of reactive oxygen species in the body increases, COQ10 concentration decreases. This suggests it is protective over mitochondrial DNA damage.

COQ10 is found in meat, fish and nuts and of course you can find it in supplemental form.

So where we always focus on macros when we consider fuelling strategies, as you can see, micronutrients are also incredibly important in the production of energy. Our canine athlete’s diet needs nutrients as well as calories.

Hydration for Dogs

Water is possibly the single most important nutrient for the body. It has a range of functions:

1) It functions as a solvent that facilitates reactions and also transports nutrients around the body.

2) Water is able to absorb heat from the processes occurring in the body, without the overall body temperature changing too much.

3) It further contributes to temperature regulation by transporting heat away from working organs through the blood. In other species it also evaporates as sweat, but dogs unfortunately don’t have this mechanism. They pant to cool down (see water loss below).

4) Water is crucial in the digestive process; it is a key player in hydrolysis, which is the splitting of larger molecules into smaller molecules (through the addition of water).

5) The kidneys also use large quantities of water when eliminating waste.

6) Adequate water is needed to ensure a balanced amount of the hormone Histamine is present.

Water loss is a natural process. Urinary excretion is the largest loss, but dogs will also experience faecal and respiratory loss.

Faecal loss is usually minimal, and only becomes an issue when there are associated health issues (diarrhoea for example), but in dogs especially, evaporation occurs from the lungs during respiration. The reason water drinking is encouraged in warmer weather is less to do with cooling dogs down, and more to replace the water lost during panting.

A dog’s total water intake comes from three possible sources:

- Water present in food,

- Metabolic water,

- Drinking water

Water present in food

The amount of water available in food, depends on the type of food it is. Commercial dry food can contain as little as 7% water. Canned foods can contain up to 84% water. Fresh food diets can be both cooked and raw. Meat in its cooked form can average around 60% water and when raw, around 75% water depending on the cut. Dogs will generally compensate for the water content differences by voluntary intake of water – you’ll notice a dry fed dog will voluntarily drink more than a can fed dog.

Metabolic water

This is the water produced during the processes that occur in the body when metabolising fat, protein and carbohydrates.

Metabolic water produced per 100g

Fat – 107ml

Carbohydrate – 55ml

Protein – 41ml

In the grand scheme of things, metabolic water is relatively insignificant as it only accounts for 5-10% of the total water intake in most animals, but it is a consideration in the canine athlete who ramps up their energy need/production.

Drinking Water

There are a range of factors that can affect how much water a dog chooses to drink, their environment, their diet, levels of exercise, overall health and life stage. Voluntary water intake will increase in warm environments and during/after exercise. This is to replace that lost during respiration, panting, and energy metabolism. One study also found that when dogs were fed a diet of 73% moisture, they obtained 38% of their water needs from drinking water. But when their diet only contained 7% water, voluntary water intake increased to 95% of their total intake.

Voluntary drinking will also increase in diets with a high salt content.

Generally, dogs are accurately able to regulate their own water levels, when they have access to fresh water.

Water loss and Dehydration

Thirst is triggered in the canine at a bodyweight loss of 0.5-1% due to dehydration. Interestingly high-protein diets can accelerate water loss due to the increased urine volume. Dry protein also increases dehydration. Water containing protein maintains levels best.

Back when animal studies were less ethical, dogs needed to be resuscitated after 10-20 days of complete water deprivation (whilst still being fed).

Signs of Dehydration

- Loss of skin elasticity,

- Loss of appetite,

- Vomiting,

- Panting,

- Pale, sticky gums,

- Prolonged capillary refill,

- Dry nose,

- Dry eyes,

- Lethargy,

- Itchy Skin

Some of these signs may be noticeable at just 5% drop in water volume.

There are also links between cognitive function and dehydration. This may be particularly relevant for the sporting dog. Dehydration has been linked to a reduced blood flow to the brain; humans appear more tired and less alert. In states of 2% water loss, there is a decrease in both speed and efficiency in psychomotor tasks. So if we want our sporting dog to be thinking straight, we need to keep them hydrated.

Where humans sweat, dogs do not (apart from low quantities from their paw pads when stressed), this means their electrolyte balance is less of a concern compared to human athletes. That said, we do need to still consider it. Excessive intake of water can deplete electrolytes necessary to heart function, nerve signalling, energy production and more. For that reason, when water intake is high, it is worth considering electrolyte intake. The main electrolytes are sodium, potassium and chloride. We often see raw fed dogs low in sodium chloride and so for the canine athlete, the addition of rock salt is often beneficial. In addition, whilst you can feed bananas to dogs, coconut water can be a helpful addition for the canine athlete. Coconut water is a source of potassium and most dogs love the taste!

Supplements for Sporting Dogs

The supplement marking is exploding and it can be hard to figure out what is worth your hard earned cash. For the sporting dog, there are some supplements that can support optimal performance.

Essential Fatty Acids

Joint degradation is characterised by inadequate production of compounds necessary to its structure, along with reduced collagen synthesis. This can be a result of physical stress (work), trauma, autoimmunity, or ageing. Here, inflammation is upregulated, creating further breakdown. It results in weak, damaged, or inflamed tissue with restricted or painful movement.

Essential fatty acids are well known to help modulate inflammatory responses found in cases of joint degradation. During the inflammatory response, certain enzymes catalyse the production of compounds which cause pain, redness, and heat. It has been discovered that omega-3 fatty acids inhibit these enzymes that result in this response.

Great sources of omega-3 fatty acids include all those oily fish like sardines, salmon, and mackerel. Some plant based oils also contain omega 3 too, hemp seed oil has a great omega 6:3 ratio. Of course you can purchase essential fatty acid supplements too.

A note to make on dry food; many dogs eating this food are ingesting far too many omega-6 fatty acids compared to omega-3 which tips the balance to a pro-inflammatory state. Inflammation is a necessary process in the body, but like goldilocks and her porridge, levels need to be just right (when fighting off a threat, like an infection, injury or alike). Yes you could feed more omega-3 to try to help balance it out, or you could, you know, consider feeding something that isn’t making your job harder than it needs to be. Think of it as removing the matches to start the fire, as opposed to trying to put it out with petrol.

Glucosamine

Glucosamine is a natural sugar that exists in the fluid around the joints, as well as in animal bones, bone marrow, shellfish, and fungi.

The body uses glucosamine to build and repair cartilage.

With age, cartilage can become less flexible and start to break down. This can lead to pain, inflammation, and tissue damage, which, for example, occurs in osteoarthritis.

It is thought that glucosamine might slow this process and benefit cartilage health.

Chondroitin

Chondroitin sulfate (CS) is a major component of the extracellular matrix of many connective tissues, including cartilage, bone, skin, ligaments and tendons.

CS is a sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) and these are key to joint health.

It is thought that CS has a number of benefits in joint health:

- CS has been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects,

- Increases type II collagen and proteoglycan (PG) synthesis,

- CS has been demonstrated to have anti-apoptotic properties,

- Functions as an antioxidant,

You will find glucosamine and chondroitin in cartilage and bone and so you could argue that a raw fed dog is getting these compounds in their diet. But supplementation is always an optio. Especially for the dry fed dog.

Collagen

Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body. It accounts for about 30% of the body’s total protein. Collagen is the primary building block of skin, muscles, bones, tendons and ligaments along with other connective tissues. It’s also found in organs, blood vessels and intestinal lining.

Proteins are made from amino acids. The main amino acids that make collagen are proline, glycine and hydroxyproline. These amino acids group together to form protein fibrils in a triple helix structure. The body also needs the proper amount of vitamin C, zinc, copper and manganese to make the triple helix, forming collagen. If these nutrients are low or in states of high turnover, collagen production and health could be compromised.

There is a disagreement over the scientific backing of collagen supplements because the body can produce it, itself. But in times of high need, there is increasing evidence suggesting a role for supplementation.

There is evidence that collagen supplementation can reduce joint deterioration in high risk groups (athletes).

In addition, data suggests that collagen supplementation can reduce joint pain and improve recovery from joint injuries.

Furthermore, athlete studies have indicated that collagen supplementation can improve muscle soreness post-training.

Collagen also has increasing evidence of reducing inflammation.

Again, you will find collagen in animal tissues that you feed a raw fed dog, but in cases of high need you may want to consider supplement, and certainly for the dry fed dog.

Whilst musculoskeletal health is important for the sporting dog, we must also consider how we can support their cognitive health. They not only need to move well, but they need to be quick thinkers and be firing on all cylinders come game day.

There is evidence for the following nutrients in supporting cognitive function in dogs:

- Antioxidants,

- Alpha-Lipoic Acid,

- Vitamin C,

- Vitamin E,

- L-Carnitine,

- Co-enzyme Q10,

- Omega-3 fatty acids: EPA and DHA,

- Phosphatidylserine,

- Choline,

- SAMe,

- Vitamin B12

A note on antioxidants.

During exercise and training there is an increase in reactive oxygen species. The body’s antioxidant system therefore needs to do its things and tackle them. There is increasing data highlighting a role for antioxidants for sporting dogs.

One study suggests that dogs fed blueberries while exercising as compared to dogs fed a control diet while exercising, may be better protected against oxidative damage.

However, another study showed greyhounds ran slower when supplemented with vitamin C, which acts as an antioxidant. The dogs ran, on average, 0.2 s slower when supplemented with 1 g of vitamin C, equivalent to a lead of 3 m at the finish of a 500-m race. Supplementation with vitamin C, therefore, appeared to slow racing greyhounds. It is proposed that high levels of vitamin C can reduce the activity of several mitochondrial enzymes (which as we know are the powerhouses of the cell).

In the human athlete world, trainers, nutritionists and dieticians are turning their back on antioxidant supplements. A review from 2002 stated the following:

“There is currently no convincing evidence to support the benefits of antioxidant supplementation in acute physical exercise and exercise training. On the contrary, exogenous antioxidants prevent some physiological functions of free radicals that are needed for cell signalling, causing higher doses of antioxidants to hamper or prevent performance-enhancing and health-promoting training adaptation such as mitochondrial biogenesis, skeletal and cardiac muscle hypertrophy, and improved insulin sensitivity. However, there remains the perception that antioxidants can counterbalance oxidative stress and benefit exercise adaptation and performance in athletes. It is likely that the negative effects of high doses of antioxidant supplementation exceed their potential benefits.”

The current school of thought is to instead include antioxidant rich foods in the diet, to support overall health and performance (like the sled dog blueberry study).

Feeding Strategies for Peak Performance

So how do we bring this all together and create a diet for the sporting dog?

Well, we could look to FEDIAF for their guidelines of feeding. They’ve developed a definition of activity levels and therefore calorie calculations based on those activity levels.

If you’re interested it's here:

But the thing we always seem to forget, these guidelines were designed for dry fed dogs. We advocate a raw food diet for all sporting dogs, quite simply because the nutrients are bioavailable and you can tailor it specifically to your dog’s needs. So the above guidelines may not suit your dog.

And remember calories were invented off the back of steam engines.

In 1819, a guy called Clément was teaching a course on industrial chemistry, and he needed a unit of heat for a discussion of how steam engines convert heat into work. He arrived at the calorie, which he defined as the quantity of heat needed to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1 °C.

We always need a baseline and so it’s worth calculating how much food your dog should be eating based on a feeding guideline, but then it's important to feed to a body condition score. You don’t want your sporting dog carrying additional weight and equally, you don’t want them starving and hitting a wall in their training.

In addition, remember that competitions aren’t won on game day. Your dog’s nutrition needs to be tailored 365 days of the year. If you are training for a comp, food intake should reflect the demands on the body. If you are on the run up to game day, even if training may be tapered, they still need the nutrients ready for game day. Post game day, their nutrition needs to reflect the recovering needs of the body. But that’s another article entirely. Do you want one on recovery in dogs? If so, let us know!

Conclusion

To summarise, in my opinion, any dog who engages in sport is a sporting dog and therefore has unique nutritional needs. Consider the nutrient needs for the sport your dog is engaging in, and ensure their diet is not only calorie dense (to suit their activity level), but also nutrient rich. They need micronutrients in their diet just as much as macronutrients.

Everyone has to start somewhere, so find a baseline bowl for your dog and then monitor. How are they performing? Do they hit a wall? Do they tire quickly? Do they suffer frequent injuries? How are they recovering? Are they hydrated? Do they get stressed which affects their nutrient usage? Then sit down and prioritise what you want to tackle first and make changes to optimise that performance marker. Once you’re happy with that performance marker, move onto the next one.

Need Some Help?

Book a Zoom consult with Dr. Conor Brady

Stay connected with news and updates!

For the most up-to-date advice, support, tips and ticks from Dr. Brady and

his team, please subscribe below .

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.